I should have known better, before I engaged with the Green Party, but Duisburg’s “Loveparade” tragedy on 24th July 2010, the German Hillsborough, unmasked politics and morale… and made me sick. The consequences changed my political as much as my professional life.

Duisburg’s Loveparade Memorial Site

Although I had almost lost my job in the early years of this century due to policy decisions by the red-green coalition government, I had not stopped supporting the German Green Party. During the Financial Crisis of 2008/9, I even decided to give in to a kind of self-blame in which I caught myself just moaning about what goes wrong in society and politics without actually doing anything about it: ‘Change the system from within!’ was the agenda I decided to follow, and I joined the Green Party in my hometown in 2009.

I should have known better, particularly after the ‘progressive government’ (we’d all been desperately waiting for during 16 years of the sluggish ‘Kohl-era’) had turned out to be a huge neoliberal disappointment. I hadn’t lost my job, not yet, but, like all over the country, the ‘Schröder-government’ had changed my workplace, the progressive and creative educational environment of a vocational education college, a “University of Industry” as one English colleague described it at the time, into a streamlined competitive ‘training agency’ forced by neoliberal law to pursue profitability rather than educational success of its students, the long-term consequences of which can be observed today.

I had joined the Green party in Duisburg after attending a public townhall committee meeting, in which local politicians decided on a catalogue of measures and projects that had been made possible by a massive investment subsidy Merkel’s first government launched during the financial crisis in order to boost the economy. No less than 60 million Euros were available for a city of half a million to spend within less than 2 years, earmarked for environmental or educational purposes in the first place, so it was no surprise that the list of projects included many schools.

As chairman of a local comprehensive school’s parents council, I was particularly interested to find out how much would be allocated to my son’s school. I was prepared for a lengthy discussion on how to distribute so much money, especially when I unexpectedly discovered that my son’s school wasn’t listed at all while almost half of the funds in the district were dedicated to one of the prestigious Grammar schools.

Yet, in the meeting, I was mistaken again as there was no discussion at all. The list was passed within minutes, just one Green Party member asked two technical questions, whereas no one wondered about the uneven distribution. I couldn’t believe it, but when I tried to ask a question as a guest, I was told that I had no right to speak for myself, so I decided to earn that right in order to pose questions nobody was apparently willing to ask. The Green Party seemed the least bad option, we shared opinions on a number of issues, and the party-political programme was closest to what I thought were the right things to do.

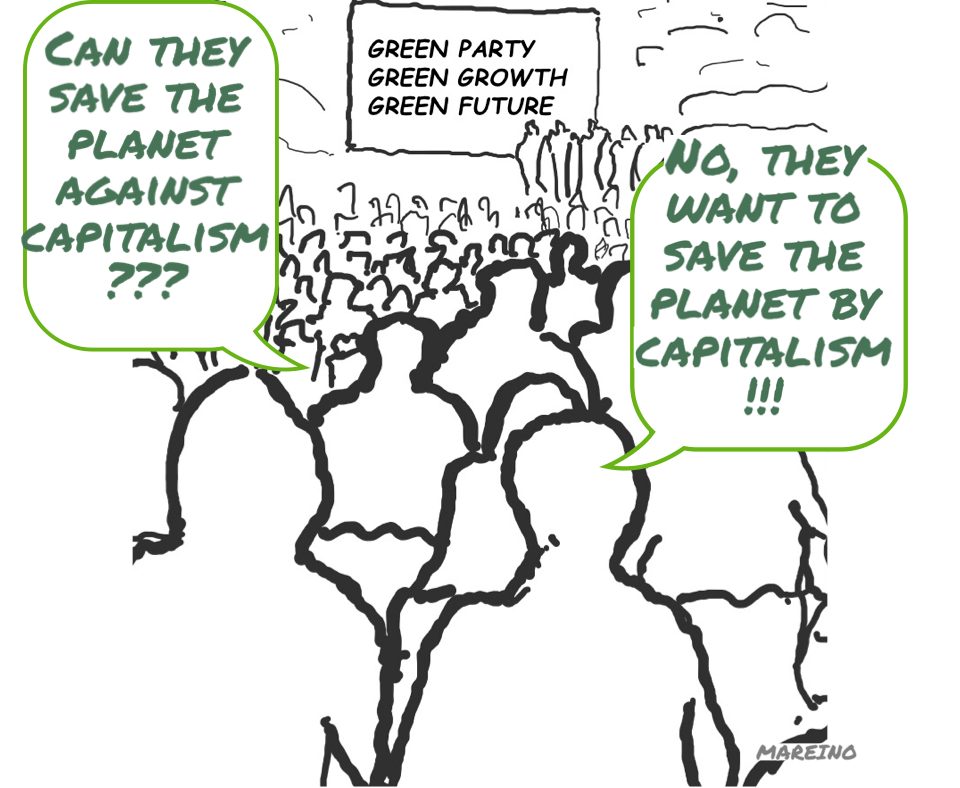

The bottom-up approach to politics as well as the Greens’ stance that an accumulation of offices would be counter-productive to grassroots democracy, a founding principle of the Green Party, had always appealed to me as much as their initial political objectives to protect the environment against capitalist exploitation and safeguard peace against mutual deterrence and military logic. On the other hand, I wasn’t naïve to believe that especially on the local level political aims could be reached without a minimal degree of professionalism and pragmatism, which I had been forced to maintain at work within the increasingly hostile degressive educational environment during ‘my’ college’s evolution into a playground of bullying, greed and competition.

After I’d been elected as ‘knowledgeable citizen’ into a seat in the Council’s Social Affairs Committee I soon found out that the (brilliant!) idea of taking the expertise of ordinary citizens into account was not more than a political fig leaf. Apart from the councillors, all those committee members were party representatives rather than experts in a particular field, and even if they were, they hardly got the opportunity to speak or ask questions, because it was up to the councillors or their deputies in the committees to speak in the name of the party, even in a small meeting. So, every topic had to be discussed in party gatherings before and after committee and council meetings, which turned out to be scarcely ideological, but incredibly time-consuming. A lot of people in those meetings, even the councillors, often didn’t have a clue of what certain topics were all about, which would be an excusable offence, had they acknowledged their ignorance instead of assuming that being elected grants wisdom.

The inner-party discussions became the more unbearable the more certain controversial decisions were influenced by party political tactics: proposals weren’t discussed on what they were about but on who brought them in. Supporting an opposing party’s motion was regularly seen as granting the opponent a political victory instead of sharing a good idea, which isn’t even reasonable in national or international relations, but totally inadequate, and not seldom pathetic in neighbourhood affairs.

My discouraging experience was that those ‘political playgrounds’ consumed the more time (we didn’t have) the less practical relevance the topics had for the citizens. So, in the decisions about allocating funds to schools there was no energy left to discuss the distribution of funds because endless hours had been used to argue about the best type of school. It was tiring, disappointing, and disillusioning, but it wasn’t a reason to quit the party soon after joining.

One needed to be equipped with a good deal of patience to be able to bear those lengthy discussions, but after all, it was believed to be a price worth paying for grassroots democracy.

Yet, the good faith I had was going to be shaken to the core a few months later.

On 24 July 2010, the ‘Loveparade’, an open air techno dance and music festival, which had attracted hundreds of thousands in Berlin, Essen, and Dortmund in previous years, took place in Duisburg as part of the Essen and Ruhr European Capital of Culture. It was the biggest event the City of Duisburg wanted to add to the annual programme schedule. It ended in a disaster, which killed 21 young people, injured more than 600, and traumatized thousands, many for the rest of their lives.

The stampede, which caused that many victims, literally happened in front of our doorstep. The entrance to the infamous tunnel, which led visitors to the overcrowded entrance to and exit from the festival area, is merely a stone’s throw away from our house. The spooky sound of high frequency techno beats mixed with the noise of helicopters circling above the festival area, and the sirens of hundreds of ambulances went on for hours, even after the horrendous fatalities had become cruel reality. It was feared there could be even more panic, and more victims, had the festival been called off. So, it continued endlessly, and the soundscape resonates in my head as soon as I think about that day of horror in our neighbourhood.

Anyone familiar with the area and its surroundings would have had no quarries commenting that the tragic incident would have been the result of organisational mismanagement, recklessness, and gross negligence by megalomanic politicians, incompetent local authorities, arrogant and greedy organizers and inundated security and police forces. But such a damning report never officially materialised while a number of investigative journalists came to exactly that conclusion.

The ‘Loveparade’ had become a topic in local politics, of course, long before the event. The contract between the organizers and the City of Duisburg had been agreed as soon as 2007, but only in 2009 it appeared in political debates, also in the Green Party I had just joined. The criticism raised nine months before the event, however, wasn’t about organisational or security issues, the details of which weren’t published until one week before it actually took place.

In the autumn of 2009, the argument was a culture clash in which self-proclaimed law-and-order watchdogs expressed their prejudices against “young, badly behaved partying drug addicts” who would “make our hometown a dance floor for 12 hours, dump piles of rubbish, and f*** off again”. A considerable number of local politicians were quite suspicious of this vibrant, noisy, and permissive youth culture of pure enjoyment. Traces of this conservative scepticism were even visible within the Green Party, although the support to go ahead with the event was overwhelming.

Yet, the outrage didn’t spill out of the traditional owners of conservatism, Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats, even if many of their Duisburg party members might have appreciated it behind the scenes. Five years before, the local political landscape in Duisburg had seen a landslide defeat of the Social Democrats, who had held the working class ‘red wall’ town since the war. The Christian Democrat Adolf Sauerland got elected as Duisburg’s Mayor in 2004, and he was re-elected by an even bigger margin in August 2009.

The previous five years he had governed relying on a council majority in a coalition with the Green Party, one of the ‘Black-Green’ coalitions in German cities that mushroomed in traditional working class towns during the final Schröder years. But unlike the Mayor, who had extended his lead, the two parties lost the election in 2009. The council coalition had ended when I joined the party, yet, political alliances behind the scenes had not. One of the leading figures of the Green Party remained in his position as Town Clerk and the Mayor’s Deputy.

Thus, in late 2009, the debates about the ‘Loveparade’, which was essentially a ‘black-green’ project, were dominated by prejudices and financial questions by those who were concerned about “taxpayers’ money” spent on “degenerated youth parties”. Considering these slanderous remarks was out of the question for a grassroots party, which the Greens proclaimed to be, and the Mayor’s Christian Democrat troops didn’t dare to ask awkward questions.

There was neither a reason for me as a young party member to get into this culture war, nor were there any serious questions about the festival that could be raised: In order to avoid prior discussions, organisational details hadn’t been made public until a week before the event, in the middle of the summer holidays, when political life in the city had come to a standstill as usual.

When we saw the map in the newspaper just before the festival, we could hardly believe what had been planned: Rather than letting people in through the wide main entrance just 500m from the central station, the visitors were led all around the huge festival area to a small entrance between the railway and the motorway tunnels, which was also meant to serve as exit. The planners had obviously wanted to keep the unpopular crowds far away from the city and shopping centre, for the ‘ordinary people of Duisburg’ to be able to enjoy their Saturday afternoon shopping “undisturbed by drunk kids”.

The festival was set on derelict land of a former railway cargo station between the eight tracks of the main railway line leading in and out of the central station, and the six lanes of the city motorway. It was, and still is today, the major local development area in the inner city. At the time of the festival it belonged to a furniture super-store mogul who had planned to build and run a huge shopping mall. He must have deeply regretted his decision to have invested in Duisburg and take some advantage out of the derelict land by letting it to the festival organisers. Not long after the disaster, he sold the land back to the City of Duisburg and hasn’t been seen in town since.

The road that led into the tunnel was fenced off on both sides on festival day, we had to walk long diversions to get out of our neighbourhood. My son, who was 12 at the time, was curious to see what the festival was like, and I agreed to take him to have a look. But as soon as we reached the fence 200 metres from our house at midday on that hot summer’s Saturday, we saw the large crowds of tattooed, colourful, vibrating bodies queuing into the tunnel, and one thing was clear: ‘No way’, we would go in there, no way!

The stampede slowly developed in the late afternoon, five hours after we had watched the long queues before the tunnel, when the music truck parade was long under way, and their sounds and beats attracted more and more people to quickly get access to the festival grounds through the deadly narrow ramp that was exit and entrance between the two tunnels. No-one of the security staff, the police or the organisers realized that hundreds of people were fatally trapped before it was too late. When they did, the ambulances onsite reacted very quickly, and alarmed a lot of additional rescuers from outside, but it took too long to get access to 21 young people who had come to party and found their death.

When the news broke, thousands, whose adolescent kids had been to the festival, the First Minister of the State of North Rhine Westphalia included, were desperately trying to reach their sons and daughters on their mobile phones. It took hours before they found out they were safe and unharmed. We were in a state of shock, when the extent of the tragedy became clear, the whole city was. Nobody expected any kind of explanation in the direct aftermath of the tragedy, the people of Duisburg just felt sadness and grief, and waited for a few words of condolence and compassion expressed by their leader.

What we heard and saw on local television instead was just the opposite: Only hours after the disaster, the festival hadn’t even finished, the Mayor fell back on the prejudiced slander of “disobeying youth”, and he dared to claim in front of the world press, which was suddenly looking at Duisburg, that the accident had been caused by youngsters breaking the rules. In another press conference on the next day, the blame game continued in an increasingly desperate attempt to disclaim any responsibility for the tragedy. When the Mayor visited the site late on that Sunday he was booed by mourners and residents.

During the following days, the hopelessly repulsive blame game became increasingly political, the wagons of his supporters were circled and drove the Mayor to stoically refuse any call, not even by the highest representatives of the state, to accept political responsibility for what had happened during an event approved and promoted by the City of Duisburg itself.

In a rare mix of clumsy words and a stubborn attitude, the Mayor had, within a few hours and days, deeply offended the victims’ families in a time of grief before they had even been able to bury their loved ones. His embarrassing insistence that he had done nothing wrong culminated in the tabloid “BILD” headlining his words “I never signed anything myself” a few days after the tragic incident.

The outrage and extent of feeling appalled was enormous. I had not imagined such a contemptuous conduct by a respected person, a former teacher and civil servant now in a high office, to be possible. I got drawn into the emerging political dispute within days, but I had underestimated the simultaneously growing hostility of the Mayor and his supporters, who saw the public outrage as a defensive battle against those who “sought to exploit the tragedy for political reasons”.

Only a few days after the incident I was shocked to realize that the battle line ran through the middle of the Green Party. Knowing that some of our party members had a close relation to the Mayor I had written an email to the local party email forum, in which I (politely) asked those in the party close to him to call the Mayor’s attention to the outrage his words and behaviour had provoked in the public, and that they should advise him to rather keep silent than saying anything more offensive.

The reaction on my email came promptly and bluntly from the Mayor’s deputy and leading figure of the Green Party, who wasn’t even in Duisburg at the time, but on holiday in Majorca: He publicly accused me of launching or contributing to a “politically driven witch hunt” against the Mayor, while “lacking the competence to contribute anything useful to the debate”.

I was stunned for a while after reading that message, but not for long. I had never been attacked in such a way for expressing an opinion and worry about such a bluntly obvious misbehaviour after a tragedy, so I fought back as publicly and hard as I could trying to disclose how much worth Green party principles and values had, when it came to political loyalties. Yet, even those party members on my side of the argument, who were (embarrassingly) trying to “explain my behaviour” to the party leaders “as a result of personal traumatisation”, were shying away from challenging their own party loyalty. As soon as I realised that political morale was a weapon against the ‘enemy’ rather than a virtue, I knew that I couldn’t stay in the party.

I left before the end of 2010, yet not without witnessing another major treason of core Green values when, after a heated discussion, the party leaders pushed a motion through, which was in favour of the communal energy supplier buying shares in one of the biggest German coal companies, which until today creates much of its turnover from buying coal worldwide and burning it in German power stations.

Though the fights within the party ended for me, public outrage in the aftermath of the Loveparade disaster didn’t. I played a part in voluntary offices, such as the parents’ council at school, where I organised a parents protest against a festive speech by the unbearable Mayor who was still in office nine months after the tragedy.

It took another year until the people of Duisburg voted on the Mayor’s future after enforcing a referendum by collecting some seventy thousand signatures. On 12 February 2012, 19 months after the Loveparade, the local newspaper “WAZ” wrote: “The spook is over (…) The people of Duisburg have impressingly drawn a line under the pathetic hustle and bustle of their Lord Mayor (…) 129,833 people have opted for the de-election (…) only 21,557 eligible voters were in favour of him remaining in office. It’s a victory for political culture…”

The feeling of relief, acknowledgement and satisfaction was overwhelming, not just for me. A deep sigh seemed to go through town. Yet, it didn’t appease my disaffection towards the Green Party. The Green Town Clerk remained in office, and the party “supported the referendum” but didn’t bring itself to discredit the Mayor let alone his Deputy.

Cured of joining a political party ever since, I haven’t even voted for the Green Party again. Maybe I was indeed traumatized, but not by the tragedy of what had happened. I was democratically traumatized by political moral collapsing in front of my doorstep like the 21 youngsters who died in the stampede. 19 months of unresolved conflict, in which my moral compass was challenged, were too much to stay sane, in a period when I also needed more and more energy at college to defend some of the main projects, that I had fought through against considerable resistance within and outside of college, because they were challenged for profitability, competition or ignorance, although they were running well.

I fell into a depression with a burnout syndrome in spring 2011, which kept me out of work for almost a year, in which some of my projects died down, and one of the young psychologists, I had employed for the educational assessment section of the department, that I had led for more than a decade, tried to establish himself as a new leader. I managed to fight him off, when I returned, but he remained a constant source of unrest within the department until I had no choice but to beat him with his own weapons, using my influence to have him fired.

Yet, the educational decline and development towards a profit centre, that had started in 2003, had progressed considerably. Although in communal hands, the college had turned into a profit seeking company which competed with private training agencies to secure government funding for training and educational measures no matter whether they made sense for the individual or not.

At the height of the refugee influx in 2015, the college failed to use its 248 student residence rooms (which had previously been profitably marketed as hotel rooms for trade fairs) as part of a wider pilot project for single refugees, in which accommodation, language training, vocational orientation and education could have been combined. I had already drafted a project outline for it, which would clearly have been a credit to the college as it had been 20 years earlier, but the times of educational progress were undoubtedly over.

Despite a few of my educational programmes still running, my professional authority had already largely faded away. Eventually, it all ended when I fell out of favour with the college director (a civil servant and administrator whose educational expertise was largely based on his own school career) due to being smeared after a speech I had given to staff of the local Jobcenter. Instead of seeking the argument after a critical remark of mine on one of the online tools used for educational assessment, one member of staff told her boss about my comment, who, in turn, reported me to my boss. The substance of my critique was never in question, it was in fact confirmed by a number of experts in the field of assessment in vocational education. But my boss had bought the tool and wanted to sell it on to the Jobcenter in a result of those unleashed neoliberal market reforms, in which “we are all competitors”, and a lot of turnover and profit is created by using public money to sell useless things from one public institution to another.

I had disturbed his plan and was given a written warning being accused of damaging the interests of the company, an allegation that would never have me back down, even though I knew that I wouldn’t have a chance to win anything more than a golden handshake in court before I had to leave.

Yet, my fight for educational opportunities has lingered on, focussing on the fate of refugees and migrants, who deserve my loyalty ever more than the toxic one, that party apparatchiks and ruthless, neoliberal technocrats expected of me.

© Reiner Siebert

One response to “My Green Trauma”

It’s quite different to hear about an event like this on the news—I remember reading about it—compared to knowing the inner stories, some of them quite shocking and very disappointing, behind it. Institutional politics and adherence to group discipline have always put me off (this feels like a curse rather than a blessing most times). I can easily relate to how you felt about all this.

LikeLiked by 1 person